The State of Women in Science in India – Not Intelligent Enough?

Saranya Manoharan

Women make up only 14% of Indian researchers, compared to the global average of 28%. Gender parity in participation in higher education has been steadily increasing, with women constituting nearly 47.6% of the total enrolment. So what explains the abysmal gender representation among researchers?

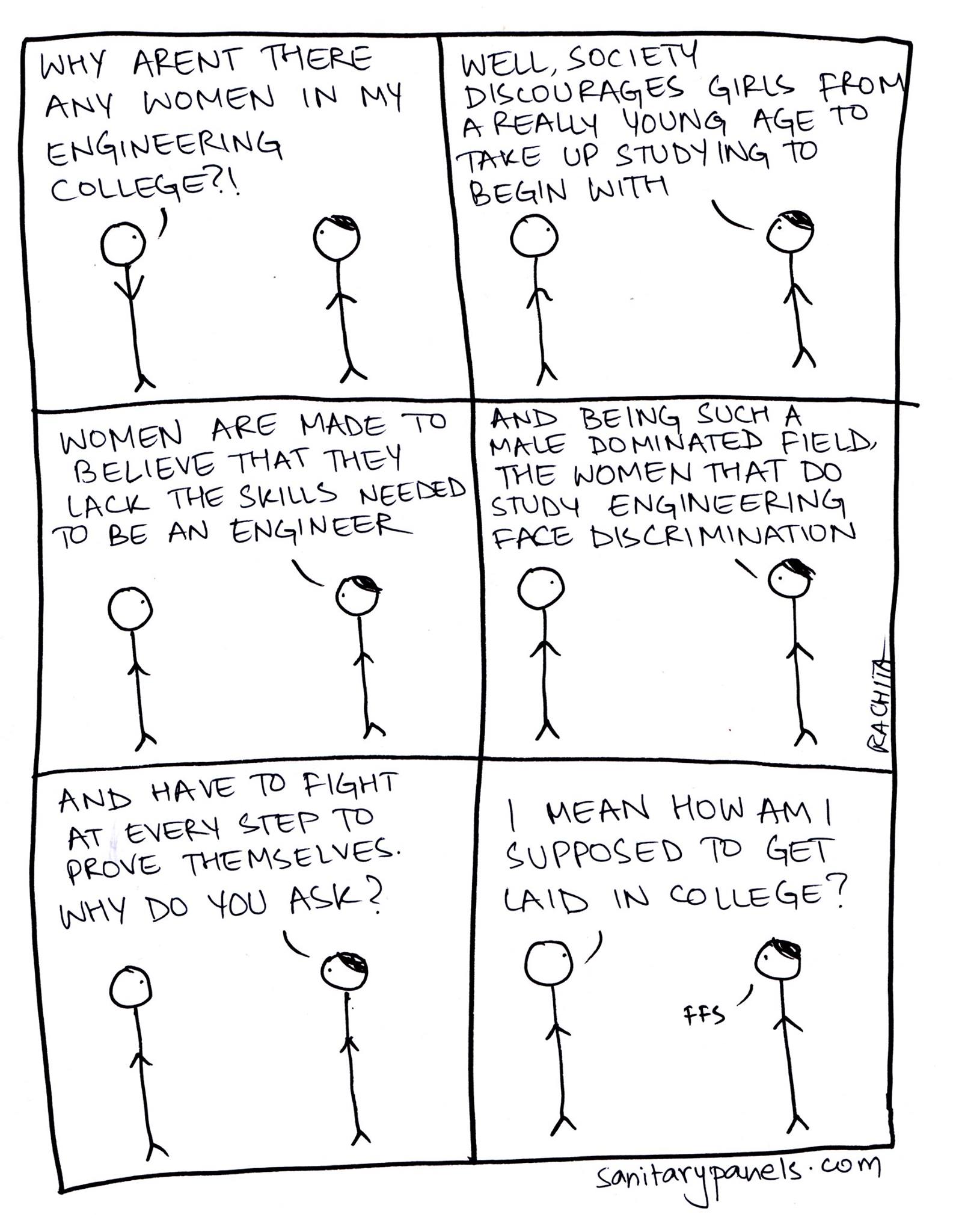

Breakup of university students by fields of study shows clear evidence of bias along gender lines. While women make up the majority of students in arts and medicine (the latter thanks mainly to the large number of women in nursing degrees), men make up the majority in science, engineering and technology, information technology and computer application, commerce, management, and law. Let us take the specific case of Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) to explore the possible reasons for the skewed gender ratio.

IITs are a group of 23 public-funded, elite higher education institutions that specialize in the areas of engineering and technology. Women make up only about 10% of the student population in these institutes, even though they make up nearly 29% of student population across all engineering colleges.

This remarkable difference is interpreted by many as evidence that women are not intelligent enough for the best universities. This is the broader perception despite the fact that girls consistently outperform boys in final school exams, even in subjects like mathematics and physics. Why, then, are there so few women at IITs?

The admission rate into IIT was less than one percent for 2018. Nearly 1.2 million students registered for the first-tier admission test for a meagre 11,000 undergraduate seats available. With such a low admission rate, coaching institutes that specialize in admissions tests into IIT have burgeoned over the last years. Surveys show that nearly 90 to 95% of students that make it to the IITs have attended classes at coaching institutes which could cost anywhere between USD 2000 and 4000.

Girls As Burden

In a strictly patriarchal society that views girls as a burden to be passed on to the husband’s family, a majority of parents would not be willing to invest this kind of money in their daughters. Even today, the primary concern for many parents with daughters is how much money they can save for her dowry (payment made to the groom for the marriage) and how soon they can get her married. However when it comes to sons, educational expenses are considered a necessary investment. This is because men are perceived as the primary breadwinners and women’s income is usually seen as additional income. Social mores also discourage women from working outside their homes.

Besides the financial component, women face severe restriction of movement. Even if a family could afford the fees for the coaching institutes, they might be reluctant to send a girl to such coaching centres because they are worried for “her safety”. Sexual violence against girls and women is highly prevalent in India, but it usually women who are blamed for having “provoked” it. Thus the responsibility of avoiding sexual violence is placed squarely on the women. Consequently, it is almost always women’s freedom that is curtailed. This translates to restrictions placed on young girls that affect their ability to attend these coaching institutes, either because the centres are too far or because the classes finish too late in the night.

Boys in India rarely face such restrictions.

Curfews for girls but not for boys

Unfortunately these limits continue to impede women while they are at university and at work as well. The most prominent example of this is the discriminatory curfews for men and women studying at the same university. While male students tend to have no or lenient curfews, female students have to confront stringent and repressive curfews which are intended to protect them. The implication is that female students have limited access to libraries, labs and other academic resources within and outside college campuses. Female students in colleges have complained about how these rules infantilize women and strips them of their autonomy, while hindering their academic and extracurricular participation.

Returning to the specific case of IITs, analyses of the student’s applications show that female students that qualify to study at IITs selected fewer options of study fields and colleges compared to male students. That is, female applicants have more constraints with respect to the branch of study and region that they can study at, thus diminishing their chance of admission. Experts say that female students, unlike male students, are often forced to study in their own hometowns, even if they can study at a better university in a different part of the country. It is also noteworthy that the female-male ratio among assistant professors in the three most popular disciplines (computer science, electrical and mechanical engineering) at IITs is a shocking 1:14.

www.sanitarypanels.com

A lack of role models for women in STEM fields is a contributing factor to the low proportion of women in these disciplines. Furthermore women in such highly male-dominant fields are more likely to report gender discrimination and sexual harassment, which again serves to discourage young girls and women from aspiring to these universities.

What is being done

Given the numerous systemic constraints that prevent women from entering STEM fields especially at the IITs, what is being done to ensure more balanced classrooms?

From the academic year 2018-19, the institutes will add seats specially reserved for female students to increase the percentage of women at IITs to 14% (from the current 10%). The hope is to have at least 20% women in the student population by 2020.

Admission statistics from 2016 show that 62% of female students who qualified to study at IITs opted out of studying at the institutes, while only 32% of male students did the same. Thus to address this discrepancy, in 2017, the administration sent a letter to all the female students who qualified in the admission test with information about an online helpdesk. The helpdesk is designed to answer queries and concern about the experience of being a female student at IITs.

While the IIT administration gradually addresses its low representation of women through measures such as these, it is obvious that the reasons for underrepresentation of women in science is intertwined with the persistent gender inequality in the Indian society.

These initiatives will only make small dents in the male-dominated spheres of academia. Equal representation of men and women in all fields will require seismic shifts in the societal perception of women and their abilities.

This is likely to take many more decades.

Saranya Manoharan is a graduate of psychology from University of Madras, India. For her undergraduate thesis, she studied gender stereotypes among school students in Chennai. Later she led sessions for a gender sensitization programme for children in India for two years. She is currently pursuing the Erasmus Mundus joint master’s degree in the psychology of global mobility, inclusion and diversity in society (Global-MINDS). She is an intern at the Centre for Gender and Science from July to August 2018. She enjoys cooking and watching TV shows with equal representation.